Bhikkhu Pesala

Bhikkhu Pesala

The Nature of Illusion

Download a » PDF file (354 K) to print your own booklets.

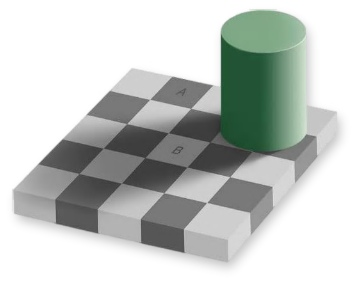

The squares marked ‘A’ and ‘B’ are exactly the same shade of grey.

Most people would insist that the square marked ‘A’ is much darker than the square marked ‘B’. It is so obvious as to be beyond question. Label ‘B’ must be on the wrong square, or the text must be wrong. There is no way that they are the same shade.

Most people would insist that the square marked ‘A’ is much darker than the square marked ‘B’. It is so obvious as to be beyond question. Label ‘B’ must be on the wrong square, or the text must be wrong. There is no way that they are the same shade.

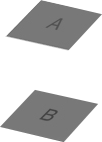

However, take another look below at the two squares in isolation. Is there any difference between the two squares there? I promise that they are cut from the exact same picture. If you don’t believe me, use a colour picker to measure the colours. The squares appear very different, but they are not.

Reproduced with permission (Website)

That is the nature of illusion. It is so convincing, until you investigate it in the right way. Illusionists make a very good living through creating convincing illusions. They become famous if they can present illusions skilfully. People really believe, at least for a moment, that the illusionist can defy the laws of nature, read their minds, or predict what they are going to do.

This is one reason why the Buddha did not approve of displaying supernormal powers. Some might think that such things are just illusions. People flock to any guru who can do such tricks. There are always two camps: the believers and the non-believers. The believers have great faith in their guru, but the non-believers think that the guru is a charlatan and the believers are just gullible fools.

This is one reason why the Buddha did not approve of displaying supernormal powers. Some might think that such things are just illusions. People flock to any guru who can do such tricks. There are always two camps: the believers and the non-believers. The believers have great faith in their guru, but the non-believers think that the guru is a charlatan and the believers are just gullible fools.

In Buddhism there are also two camps: those who understand the Dhamma, and those who do not. I will try to explain the Dhamma. Please try to understand it.

Illusion is called “vipallāsa” in Pāḷi. It is of three kinds:

- The illusion of perception,

- The illusion of thought, and

- The illusion of view.

The Illusion of Perception

The Illusion of Perception

The illusion of the grey squares is an illusion of perception. The squares are exactly the same shade of grey, but due to the context in which you see them, the square marked ‘A’ seems to be much darker than the square marked ‘B’.

Another example of this illusion is a scarecrow. If a farmer sets up a scarecrow in the middle of a field, birds and wild animals stay away, because when a man is in the field they are afraid to approach. They perceive the scarecrow as a real man. If they were to approach closer and check it out, they would not be afraid of it.

The Illusion of Thought

The Illusion of Thought

The illusion of thought is like illusions created by magicians. By making you pay attention to some details and not to others, a magician can make you believe that he can read your mind to know which card you have chosen, etc. It is also very convincing, even though one knows that it is just an illusion.

Another example is the various kind of scams that con-merchants use to prey on innocent people. If one does not know about such scams, it is very easy to be fooled by them. If one knows about a particular scam, one can see through it at once.

Take pyramid selling for example. Anyone who understands the mathematics behind pyramid selling will not be taken in by any such scam. Those who participate in such pyramid selling scams are either dishonest or very naïve.

Take pyramid selling for example. Anyone who understands the mathematics behind pyramid selling will not be taken in by any such scam. Those who participate in such pyramid selling scams are either dishonest or very naïve.

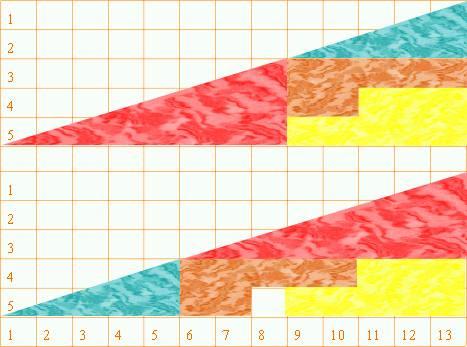

Look at the diagrams

The bottom one was created simply by copying the top shapes to the bottom. Nothing was resized, just the position was changed. Where did the white space come from? Count the grid cells, they are all the same size, and are not distorted in any way. In each case, the large triangle fits on a grid of 5 rows by 13 columns. I was baffled when I first saw this puzzle. Now that I know how it works, I am no longer deceived by it.

The Illusion of View

The Illusion of View

The illusion of view is like the case of a man lost in the desert, where there are few distinguishing landmarks. A man may become disoriented and believe that he is travelling north towards safety, when, in fact, he is travelling south, deeper into the desert. The harder he tries, the farther astray he goes. How pitiful his plight is!

Nearly everyone in the world is living under the spell of the illusion of view. They think they are right, but they are wrong. They are busy working for aims that are empty and futile. Because they have insufficient knowledge of the Dhamma, they do not know what to strive for, nor how to strive. What they perceive as happiness, the wise perceive as suffering. What they perceive as suffering, the wise perceive as happiness.

Just look how hard people struggle to get a new car. They work overtime, cut down on other spending. Then they have to pay for insurance, road tax, petrol, maintenance, parking fines, congestion charging, etc. They use a new car for ten or fifteen years, then they have to struggle again to take it to the rubbish tip. If only they had struggled to remove their desire in the first place.

It is easy to be wise with hindsight, but illusions and wrong views are a serious problem. It is due to such illusions that people have to suffer so much. When their loved ones die, or things do not work out as they planned, people have their illusions shattered, and have to suffer terribly. It is not easy to see things as they really are.

All suffering has its root in illusion. The Buddha taught that craving is the cause of suffering, which is right of course, but it is the proximate cause, not the root cause. Why do we get attached to things, to people, and to views? The root cause is ignorance (avijjā), which includes illusion (vipallāsa), delusion (moha), wrong view (diṭṭhi), conceit (māna), and personality view (sakkāya diṭṭhi).

How Illusions and Wrong Views Arise

How Illusions and Wrong Views Arise

It is vital to understand how illusion, delusion, and wrong views arise. Not even trying to understand means the darkest ignorance. It is not that you do not know what the Buddha taught — you know very well what you should do — but you do not want to know, so you ignore what he said, and just continue your life as usual. That is what ignorance is — a kind of “bury your head in the sand” mentality. It doesn’t mean just a lack of knowledge. One may have heaps of knowledge, but without insight and wisdom one remains ignorant.

There is a saying in Burmese: “One visit to a funeral is better than ten visits to the monastery.” You visit the monastery, you listen to Dhamma talks, discussions, and lectures, and perhaps you read Dhamma books too, but nothing changes very much. Why is that?

It is due to the profound nature of illusion. The illusions of permanence, pleasure, and self are just too convincing, too real. You cannot even imagine that they are illusions. Just like square ‘A’ and square ‘B’ — nothing will convince you until you see through the illusion for yourself.

When you go to a funeral, it is usually the funeral of someone known to you very well. If not a relative, then at least it will be a close friend. Then you may realise something about life that you cannot read in books, and you cannot hear in talks. When you see that things are impermanent, painful, and not subject to your control, you gain some faith in the Dhamma. “Only seeing is believing,” as the saying goes.

In the Dhammapada it says:

“In the unreal they imagine the real, in the real they imagine the unreal — those who abide in the pasture ground of wrong thoughts, never arrive at the real.” (Dhp v 11)

To arrive at the real, which means to attain nibbāna, one must practise insight meditation. There is no other way. One may gain some knowledge and wisdom from reading books and listening to talks, but it is superficial knowledge and shallow wisdom, not deep knowledge or profound wisdom.

One can study nautical science and meteorology, or one can sail a yacht across the ocean. The kind of knowledge that one gains in each case is totally different. Theoretical knowledge is very useful, even essential if one intends to sail alone, but it cannot compare to practical experience.

Insight meditation is similar. Those who read books about meditation and practise for an hour or two when they feel like it, have not even begun to meditate properly.

How to Remove Illusion

How to Remove Illusion

To understand deeply what the Buddha said about the nature of illusion, one must practise meditation continuously for weeks or months, not just for a few hours. Within a single ten-day course one might obtain some insight — someone with stable morality and good concentration might do that. However, one course will not be enough. One will gain some faith in the practice, but one’s insight will still be very shallow and unstable after just ten-days. All too soon, illusion will reassert itself, and one will be in the same boat as non-meditators, swept around here and there by worldly currents. However, if one practises hard, not just for one course, but for five or six courses, and keeps up the practice at home too, one’s attitude will change.

Take a look at the triangles again, but this time with the straight line against them you can clearly see the difference. Now you can understand why the lower ‘triangle’ has a greater area than the top one. It is only about 1.5% difference, so when that difference is spread out along the longest side, you do not even notice it.

The Tangents

The Tangents

Red triangle = 3/8 or 0.375

Big triangle = 5/13 or 0.385

Blue triangle = 2/5 or 0.4

Once the theory behind this illusion has been explained, or understood by one’s own reasoning, it is impossible to be fooled by it again. One would have to forget the explanation to be baffled by this puzzle as one was before.

The difference between meditators and non-meditators is like the difference between the two big ‘triangles.’ To the casual observer, the difference is imperceptible. Someone who is perfectly straightforward will easily notice the difference, but the minds of non-meditators are not straight enough to distinguish right from wrong. That is why they don’t meditate, and also why they think that they don’t need to meditate! They think that meditation is a waste of time. What a pity. Thirty, forty, fifty or more years of their life has gone by, but they still cannot think straight. They haven’t even set one foot on the Noble Eightfold Path.

Let me remind you what it is: Right view, right thought, right action, right speech, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration. The first two and the last three are all about mental development or meditation. They must be cultivated in conjunction with the other three, not afterwards when those three are perfect. Without meditation, morality will never be perfect.

Non-meditators may protest, “I keep the five precepts and support my family. Why do I need to meditate? I’m so busy!” but they don’t even keep the five precepts. They cannot, because they cannot control their minds properly. They are not free from illusions.

Even shallow insight is better than none at all. If meditators attend one course after another — at least one ten-day course every year — sooner or later they will gain some useful insight, and really set foot on the path to nibbāna.

Those fortunate and gifted individuals who realise nibbāna, obtain something unimaginably rare and precious. You cannot compare their insight to diamonds or rubies, it is far more valuable than that.

Their escape from suffering in the lower realms is secure. The most deeply-rooted illusion of self, which has accompanied them throughout the eternity of saṃsāra, is completely destroyed. Never again can they be fooled into regarding any conditioned thing as permanent or reliable. That illusion is shattered, so they no longer think in the same egotistical way that ordinary people do. They have overcome all three illusions of perception, thought, and view regarding the so-called ‘self.’

The illusion of perception is very difficult to overcome — as the illusion of the grey squares demonstrates. Even though it has been fully explained, and you have seen that the squares are the same shade of grey when taken out of context, when they are back in context again, they still look different, just as they did when you saw them in context for the first time.

Even a Stream-winner is not free from illusions of pleasure. A Stream-winner is only free from wrong-view, the misperceptions that makes right seem wrong, and wrong seem right.

The Dangers of Illusion

The Dangers of Illusion

Ordinary people see no harm in drinking a little, and the foolish ones see no harm in drinking a lot. Even telling lies is unavoidable for them. It is just a ‘white lie’ or ‘the lesser of two evils.’ Buddhists don’t usually rob banks, but as for illegal use of copyrighted software or other dishonesty, their answer is, “Everybody does it.”

Illusion deludes people completely. It is wise to realise that one is deluded, or even a bit insane. If one imagines that one is perfectly sane, normal, and happy, then one is in serious trouble. Not only people with emotional problems need to meditate, everyone needs to meditate — even Arahants do it.

As in the well-known saying, “You do not have to be mad to work here, but if you are, it helps a lot” don’t assume that you know it all. When it comes to meditation, you know very little until you are enlightened, and then you know nothing! That is not just some Zen koan. The aim of insight meditation is to remove conditioning. It is a gradual process of cultivating the art of non-grasping — learning to keep the mind completely open and receptive to the way things really are. Each breath and each step that you take is completely new, and has never arisen before. After it ceases, it will never arise again. Yet you perceive, think, and believe that you are breathing and walking. It is not so. The breath arises and passes away dependent on conditions. The steps arise and pass away dependent on conditions. In reality, there is no one who is breathing or walking — no one who is thinking or talking.

The Development of Insight

The Development of Insight

Mental and physical processes arise and pass away, in fantastically rapid succession. Most people are totally unaware of this fact. They see these processes as a continuous person, as a ‘self,’ as ‘me,’ as ‘I,’ or ‘mine.’ They do not perceive the discontinuity. To perceive this truth clearly means the knowledge of arising and passing away, which is deep insight. Lazy meditators cannot attain it. A part-time meditator cannot attain it either.

At higher stages of insight, the ego begins to dissolve, and the meditator gets frightened by what he or she discovers. Mental and physical phenomena are seen as terrifying and unreliable. One must go beyond this to realise nibbāna, that is why nibbāna is so elusive.

This is just some theoretical knowledge for your education — to whet your appetite so that you can appreciate better what should be done to overcome illusion.

Please try to meditate seriously to gain some genuine insight. Even the lowest stages of insight knowledge are not perceived by non-meditators, who cannot understand the special value of this life.

To be a non-Buddhist, but to live an honest life, is better than to call oneself a Buddhist, but to be ignorant of the Buddha’s teaching. Why is that? A non-Buddhist will not misrepresent the Blessed One by saying, “There is no need to practise meditation. Just give alms to the monks, respect your parents, observe the five precepts, and maintain the Buddhist traditions.” Such people will swear that black is white rather than admit the truth.